But, after I deleted that and scrolled a bit more, I did find this:

I love music so much that I subscribe to not 0, and not even 1, but 2 streaming music services: YouTube Music (blech, what a name) and Apple Music (hardly better).

Why would I do such a thing?

Here are some notable features of the 1994 Axiom Ambient album, an incredible victory over copyright limitations in its pleasing combination of diverse talents and tools:

This, and I have a wife with better musical taste than me who is willing to explain to me how I can listen to her playlists on the vertically integrated, corporate pimping, payola lined hellscape that is Apple music.

There are three more Khaleds and three more “Khaled”s, and one more Eilish on this landing page than I want despite being logged in to FruitTunes:

Suppose there is a future for non-corporate musicians in large numbers making living wages by streaming music (doubtful). Maybe, and this is a big stretch, one of the ways I can help get there is by spending money on two services, so Bill Laswell can get a few cents towards his month to month (he could be loaded, I have no idea).

Like I said: doubtful.

Sharky Laguana, if that is your real name, you get at least two things wrong in your article about streaming music.

We can do number 2 a couple of different ways.

Your Rdio spreadsheet example only works, with its difference between columns, on the premise that Brendan is the only person paying each of the artists for which the inequity is great.

Let’s do an example. Suppose that everyone, on average, has the same musical tastes, and listens to artists at the same rate. I know that’s not true — but if it were, then clearly there would be no difference between the Subscriber Share and Big Pool methods as you call them:

1/8x +1/8y = 1/8(x + y)

Your argument requires the premise that distribution of artists listened to is very different at different streaming levels. Do you know this? If so, how?

Finally, I find it funny that you think that these companies aren’t aware of the problem of stream falsification, and aren’t working on addressing it.

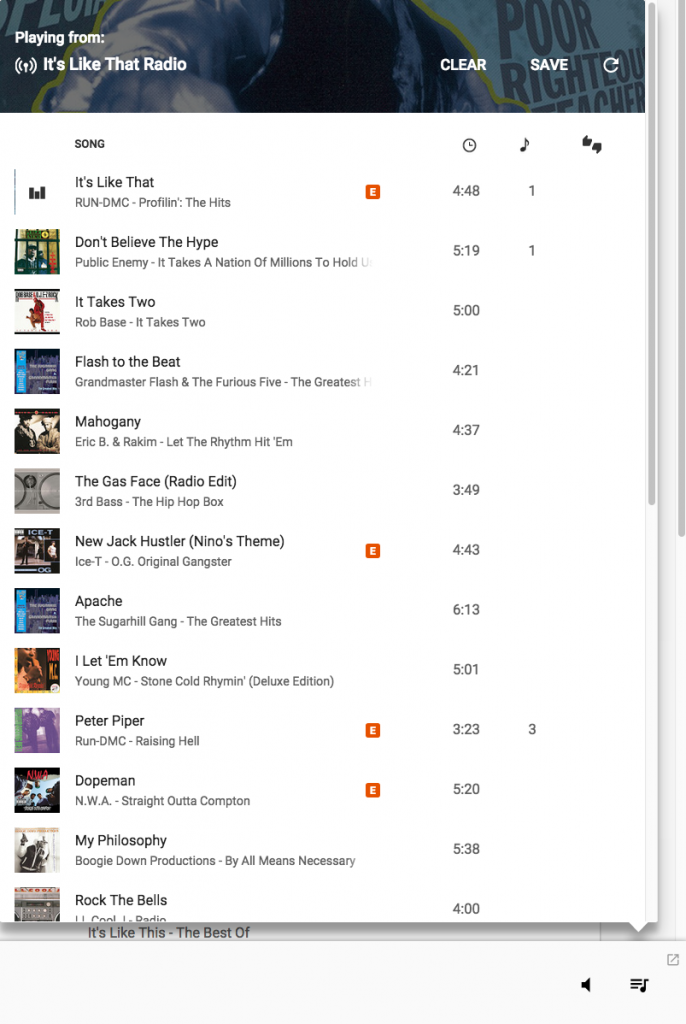

Anyone can google “It’s Like That” and find out that it’s a 1983 song by American hip-hop group Run-D.M.C.

That’s the second result I get for it. The first is a video for the 1997 Jason Nevins remix of the song.

Suppose I ask Google Music to “Start radio” for that song. Since it doesn’t have that song, I have to Start radio for the original 1983 version. What does “Start radio” actually mean? You can find the vague answer here.

Google should know that I like the 1997 version — after all, YouTube’s data is their data. If Google Music were interested in clever music discovery, it wouldn’t just use Wikipedia facts (American hip-hop, 1983) and build a playlist of the top 40 songs that more or less meet that description. Unfortunately, sometimes that’s exactly what it does. I’m pretty sure that every one of these songs was top 40 American R&B in the 1980s.

Wouldn’t it be nice if it included, say, some “electro-hop“?

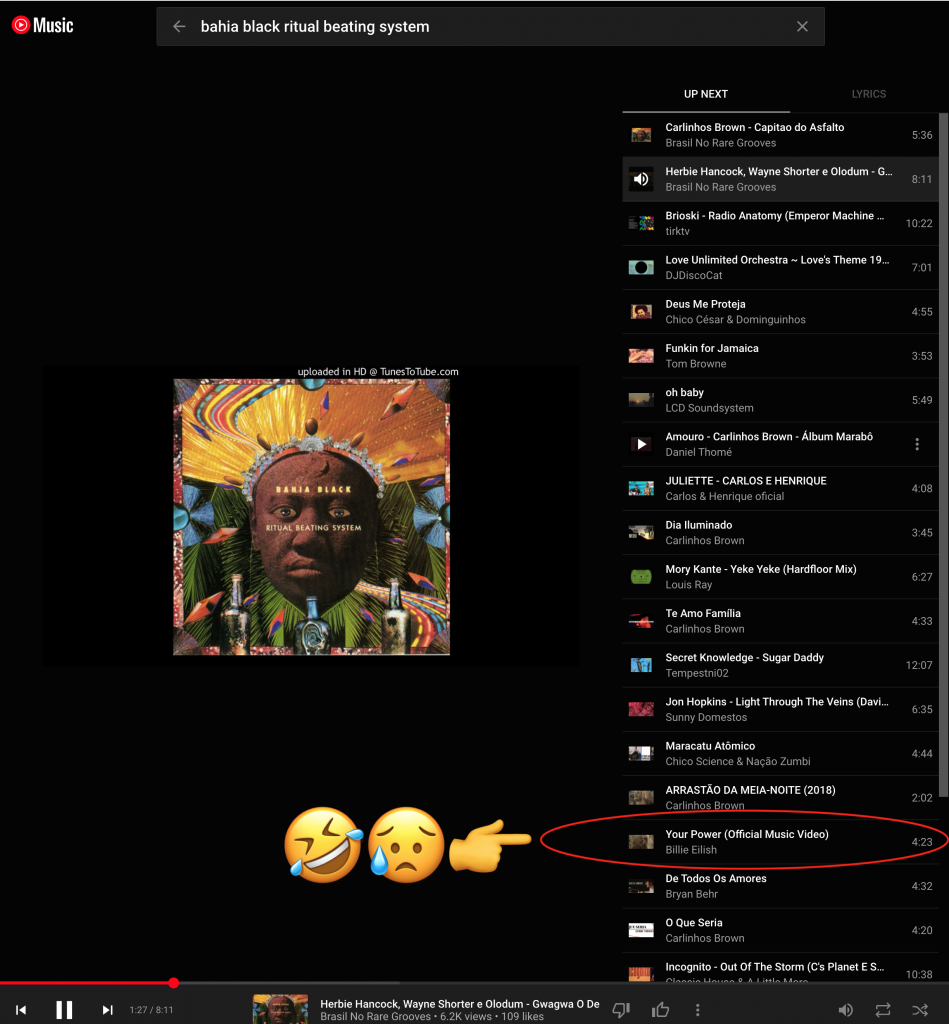

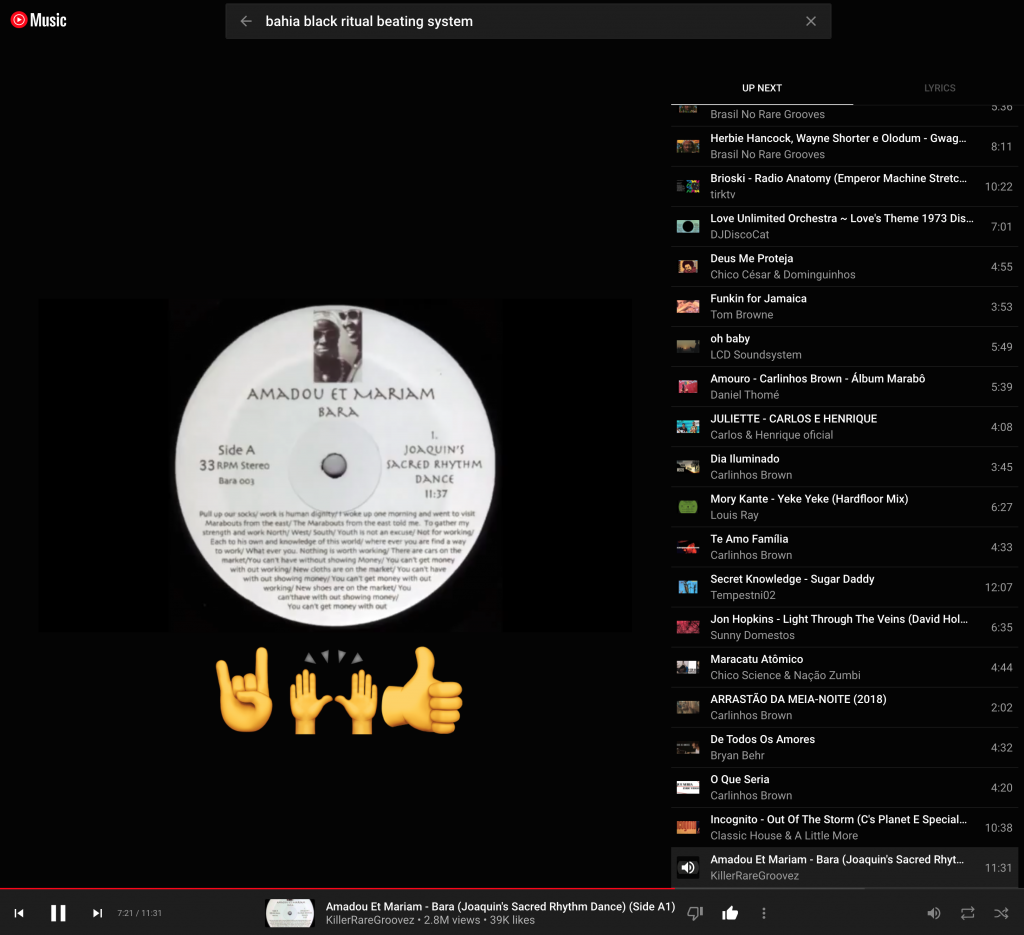

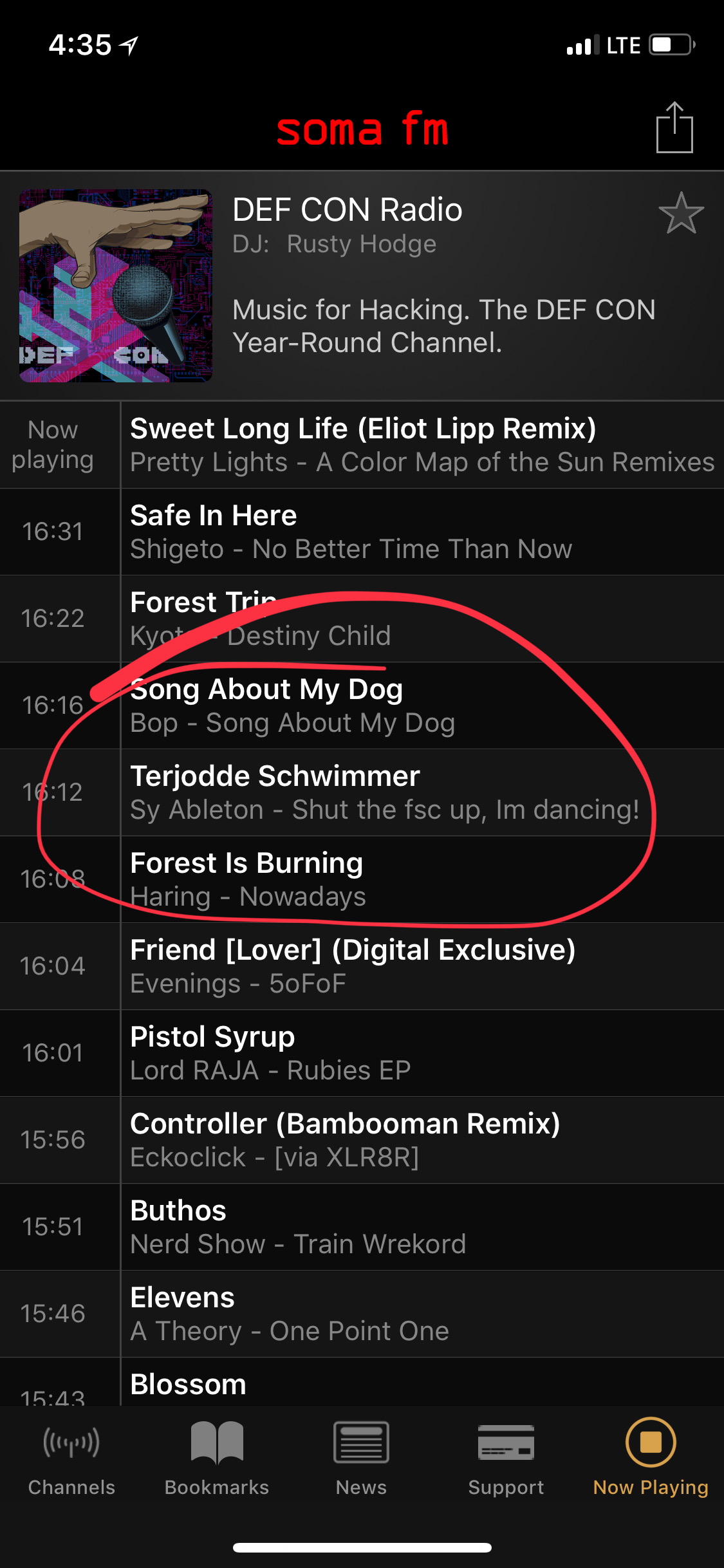

When I did “Start radio” on my phone for Farbwechsel by Myrone Aiden, something strange happened. Check this out:

This radio station contains music that cannot be grouped together by era nor, therefore, by genre. That’s a funny thing about popular music: its genres are very specific to decades. Maybe that will change now that our corporate overlords are less in charge of defining them than they used to be.

There’s a thread running through these tunes. I’m not sure what it is, but the fact that Todd Terje is making light-touch remixes of Roxy Music and collaborating with Bryan Ferry to do covers of Robert Palmer suggests that it’s there.

This playlist contains music from a bunch of different decades/genres/styles/countries. It is even largely weighted towards artists that I’m familiar with and like. I see only one song that I’m sure I won’t like, having listened to its album on a road trip recently. There’s even some songs where I want to cast a sly glance in Google’s direction and wonder how it knows me so well. (I know how it knows me so well, and the answer is exactly as creepy as you’d expect — it watches us.)

Google is a company that is defined by “being good at things that you need crazy amounts of data to be good at.” The technical term for ‘crazy amounts’ is ‘web-scale data.’ Their strengths at search, advertising and translation (among many others) are defined by their effective use of web-scale data.

Wouldn’t it be amazing if Google Music’s discovery tools always made such effective use of web-scale data? Of course, all data mining/machine learning algorithms need to be tuned by someone knowledgeable.

Google, here’s my suggestion: if you haven’t already, hire the folks at Soma.fm to do quality assurance for music discovery on your service for a while. They are in the (not-for-profit) business of defining new genres.

Right now their website says they need $940 by the end of the day. You can afford that, right?

Google Play Music All Access is a terrible name for a service. I wonder what Apple would call a similar service?

This is a non-commercial ‘mashup’ of tracks by Apple Music employees/contractors Trent Reznor (“Nine Inch Nails,” 1994) and Tahliah Debrett Barnett (“FKA (Formerly Known As) Twigs,” 2014). The tracks have the same name, ‘Closer.’

The point of the mashup is to demonstrate identity of underlying composition: verse/chorus/bridge/breakdown size and ordering; key; and theme. It is also an example intended for use in Dalhousie University ASSC/FASS 1200 “Creativity In the Internet Age.”

Under the Canadian Copyright Act 29.21 (1) current as of 2015-06-09, a work is not an infringement of copyright so long as it is

-done solely for non-commercial purposes;

-the source material is mentioned;

-I had reasonable grounds to believe that the existing copies used were non-infringing;

-Trent and Tahliah won’t lose a lot of money/fame/power as a result of this work.

I don’t know how to make money by posting music on the internet; I do believe the existing copies were non-infringing; and, Trent and Tahliah will be just fine.

Before I get to why, I have a question: will Apple Music Connect, “a place where musicians give their fans a closer look at their work, their inspirations, and their world,” that has the words “zero interference” front and center, allow artists to post mashups? Later I’ll remind you why you should care about the answer to this question. I think that copyright as it is currently conceived in Canada and the U.S. is bad, and is being changed bit by bit to help rich people and corporations, and to hurt creativity, young people and music. But I still ❤️ copyright, and I’m going to try and explain why. The easiest way to do so is with a story.

Here’s a little story I’d like to tell about three bad brothers you know so well. Had this been an academic publication, I would have had to post a footnote or something that contains the following facts:

The overall reason I ❤️ copyright is that without it, the story of The Beastie Boys could never have happened. Here’s why.

Three middle class Jewish New Yorkers, in the midst of a short teenage punk rock career, started recording expensively produced, full of studio-quality mixed samples of other artists. They didn’t ask permission or pay any money for the samples. I know what you’re thinking — their rich parents probably paid for everything. Not true! They had around $40,000 with which they could hang out, not go to school, and work at some creative ideas. “Well how did they get that $40k?” you ask.

They made a call to a Carvel ice cream shop, recorded their crank request for prostitution services, and placed that recording over some beats from a toy. That track became the title track for an E.P., “Cooky Puss.” Another track on the E.P. was a reggae/dancehall satire. Then they circulated the E.P. to their punk friends. Someone knew a guy (it almost certainly had to be a guy back in those days) and, lo and behold, British Airways sampled the Cooky Puss E.P. for one of their television commercials. This was back in the days when broadcast TV was BIG. Imagine Super Bowl-sized viewing audiences being advertised to every week.

The BBoys lawyered up, sued British Airways for — wait for it, copyright infringement — and got paid. $40,000 to be exact. A biographer says with the money “the Beasties bought autonomy” and quit their day jobs to make music full time. They were able to jam in their own pad, using the toys available at the time, and give us what Rolling Stone has called the greatest debut album of all time.

1. I ❤️ copyright because it is the kind of law that let the Beastie Boys, unknowns with very little power or money go up to British Airways and say ‘yo, where’s my money?’

And then the world was blessed with Licensed to Ill. Already you should be thinking ‘WTF? I thought those Beastie Boys were the biggest copyright violators around.’ In a sense, you’re right. There were at least a dozen unlicensed samples in that album by such bands as

Led Zeppelin, Bo Diddley, Juice, Joeski Love, Beside, Bob James, Kool & The Gang, The Jimmy Castor Bunch, Doug E. Fresh and Slick Rick, Kurtis Blow, Trouble Funk, Funk Inc., Run-DMC, War, Fat Larry’s Band, Barry White, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Schoolly D, Billy Preston, Jay Livingstone, The Steve Miller Band, Cerrone, The Russell Brothers, Ralph MacDonald, Black Sabbath, The Clash, Wild Sugar and Sugarhill Gang.

And yet despite Licensed to Ill being a massive commercial success, the Beastie Boys weren’t sued into oblivion. What gives!?

Whatever copyright was in the mid to late 1980s, it stayed that way until at least 1989. That year the Beastie Boys released their follow up to Licensed to Ill, titled Paul’s Boutique. This album is widely regarded as a ‘critical success’, despite being a ‘commercial failure’ at the time. Let me repeat that: Paul’s Boutique is contrasted with ‘the greatest debut album of all time’ as being critically well-regarded. Here’s Rolling Stone’s review. Notable in that review is their consideration of the vast number of samples on the album: “If you can recognize them, fine, but they stand on their own; it’s no more thievery than Led Zep’s borrowing from Muddy Waters.”

The complete list of samples on Paul’s Boutique has been crowdsourced and posted online at www.paulsboutique.info. Wikipedia describes there as being 105 samples on the album which were in fact cleared for use from their copyright holders, costing $250,000. A recent study suggests that if current copyright law prevailed at the time the album was recorded, then with the sales Paul’s Boutique generated when it was released (2.5m) it would have been a net loser, to the tune of -$20m USD. If copyright then was like copyright now, that album could never have been made.

2. I ❤️ copyright because there’s a version of it according to which making new music with other people’s music is OK, or at least not limited to the rich and powerful.

Sampling is one way in which the Beastie Boys interacted with other musicians and music across vast reaches of time and space. Here’s some others. Did you know that LL Cool J was discovered and had his career launched by Adam Horovitz (“Adrock”) of the Beastie Boys in 1984? Did you know that the song Slow and Low, on Licensed to Ill, was gifted by Run DMC to the Beastie Boys? It’s true! Here’s the BB performing it live in 1987, and here’s Run DMC’s demo version. Wow, those sure are different!

Lots of different musicians borrow music, and have their music borrowed. There’s Led Zeppelin, who were sampled all over the place on Licensed to Ill. Not only are they doing OK, they’re no strangers to musical borrowing! Borrowing happens across genres and decades. Listen to how this sample from Ronnie Lawson was used in Shake Your Rump and in a forgotten techno record from 1995. Copyright isn’t just about money — it’s about a law that says that you have the right to be recognized for what you made.

3. I ❤️ copyright because it brings past and present together, builds bridges between culture. Hey, wait a minute. I thought copyright was all evil and stuff.

It is! We live in a time in which the toys we have available for making new out of old and sharing with others is cheaper and easier than ever before. Make no mistake — music has always been about making new out of old, and sharing with others. But governments are making it harder than ever to do both of those things. We live in a time in which copyright is a wild beast, with the potential to destroy the very things it was created to encourage. Copyright as it is now would have killed the Beastie Boys in their cradle, after they spent all of their $40k on lawyers and copyright permissions.

Here’s another story, but a more recent one. An 18 year old French kid (Madeon) posts a video on YouTube in which he uses samples from his favorite pop artists to make an original composition using an electronic toy. He posts a bunch of his music to an online community (SoundCloud). The community flourishes: artists starting out post remixes, mashups and other forms of new out of old. But as soon as there’s money to be made, down drops the copyright hammer. I encourage you to read Madeon’s tweet about what Sony is doing to SoundCloud there. Do you really think that Madeon could have gotten his start on Apple Music Connect? Do you think they’ll let musicians sample and post?

I want to end on a positive note. Apparently, in Adam Yauch’s (MCA’s) will, there is a provision that prevents his musical work from being used for advertising. Legal experts disagree on whether it is enforceable, but they agree that the fact that he has a chance for a say at all is thanks to copyright law. Not allowing music by the Beastie Boys to be used in advertising has been a consistent position since the beginning with the British Airways incident, through the thing with the startup trying to sell egalitarian engineering toys, through to the every end of the Beastie Boys.

Whatever copyright is, or is becoming, it makes it possible for people to say how their creative works will be used. Therein lies its central tension. If it gives artists too much power, then it hurts the drive to create. Recent copyright hacks like the GPL and Copyleft couldn’t exist without copyright law. When I say they are ‘copyright hacks’ what I mean is that they let artists release creative works that can be used to make other creative works, but (in some versions) can’t be used for advertising.

4. I ❤️ copyright because it lets people (including, maybe, even ones who have left us) say ‘I don’t want my music to be used to sling other stuff.’

Copyright is changing. Recently, a case was won in which creative elements from the underlying composition were judged to have been copied — no samples, but bits of style and melody. In the words of the lawyer representing the alleged copiers, this could “have a chilling effect on musicians who try to emulate an era or another artist’s sound.” If this stands, we could be entering a copyright regime that would have killed Led Zeppelin in their cradle. Still, we can dream.

Summarizing, I think we should all ❤️ copyright. Some of the most well-loved music of all time wouldn’t exist without it. It is a weapon that can be wielded by all, including the less powerful. It lets people be recognized for their contributions. In some versions it closes divides between people, and lets artists have a vision for how their art will be used.

Last year I posted another story that couldn’t have happened without copyright. For the record, when I asked John Harris if he minded being sampled without his permission and used in a musical recording heard by millions of people, without even getting credit, he said he was just glad that his poetry was being heard.

TribalMixes is a “private torrent tracker” that’s been around since 2006. I joined in 2007.

It’s a contemporary analogue to the old scenes where folks would tape record radio broadcasts or live performances and then share them with each other. One big difference now is that the copies are all perfect, and way easier to share.

The way private torrent trackers work is that they enforce a ratio.

They know your IP address, and only permit people who are also registered and visiting their website to share the torrented files that they track. The website knows exactly how much data you’ve downloaded, and how much you’ve uploaded. In this case, the first has to be at least 0.4 of the second, or you’re cut off.

There’s an elaborate system of games (e.g. raffles) and gifts (free upload credit for visiting the site), and they also reward donations with upload credit.

At Durty Nelly‘s there’s a machine that looks like an ATM. It’s very easy to use.

Penny Arcade explains it best.

Having donated my $5 to the site, it appears I have an invite to share. Hit me up in the comments if you’re interested in joining it. To see if it’s up your alley, here’s the last ten things to be posted there as I’m writing this: